Related Techniques

There are a number of X-ray techniques that are related to or share some characteristics with X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Most of these involve the excitation of core electronic levels or are sensitive to the chemical state or local atomic coordination around a particular element selected by an X-ray absorption edge or emission line.

X-Ray Emission Spectroscopy

There are various experimental schemes for detecting X-rays that are emitted from a sample. We take the liberty within this wiki to define X-ray Emission Spectroscopy (XES) as measuring the X-rays with an energy lower than the excitation energy, e.g. inelastically scattered, and with an instrumental energy broadening that is on the order of the core hole lifetime broadening. This article only discusses hard X-ray XES. The 1s core hole lifetime broadening of 3d transition metals is around 1 eV and increases to several eV for the L lines of 5d elements[1].

XES is a secondary process. First, a core hole is created by, e.g., the absorption of an incident photon. The core hole decays after a time \(\tau\) (the core hole lifetime) and the energy that is freed upon this decay is either transferred to an electron (Auger decay) or to a photon (XES). With a tunable incident energy we can distinguish between resonant and non-resonant XES. The latter is usually referred to as X-ray fluorescence. When the incident energy is tuned around the resonances of an absorption edge we can observe a variation of the XES spectral shape depending on the incident energy. Resonant XES can be described within the theoretical framework of resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS). XES, RXES and RIXS have been reviewed by several authors.[2-5]

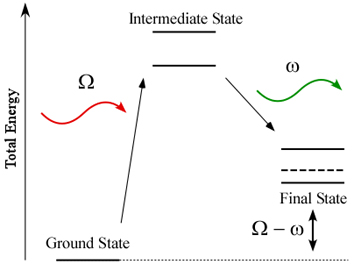

The intermediate states in the image below are the excited states that give rise to an X-ray absorption spectrum.

Intermediate and Final Electronic States

XES with lifetime resolution is sensitive to the local electronic structure and coordination of the emitting atom. It provides information that is complementary to XAS in particular with respect to electronic structure.

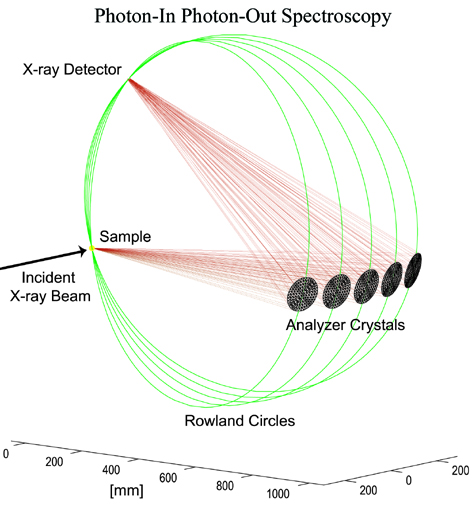

XES in combination with XAS at a synchrotron radiation beamline is a photon-in photon-out technique. The hard X-ray probe makes all techniques suitable for in-situ (operando) studies and experiments under extreme conditions (e.g. high pressure). XAS-XES can be performed within the same experimental setup.

Instrumentation

Solid state detectors with an energy bandwidth > 150 eV for the Kalpha emission lines of the 3d transition metals cannot be used for X-ray emission spectroscopy with lifetime resolution. Bragg optics using a perfect single crystal monochromator (like the beamline monochromator for the incident energy) can achieve the required energy resolution. Several geometrical schemes to realize such a secondary spectroscopy have been thought off and implemented at synchrotron radiation sources as well as laboratory X-ray and/or particle sources (e.g. protons):

Johann

Johansson

van Howe

The geometries are based on the Rowland circle. In Johann and Johansson geometry the diameter of the Rowland circle is defined by a spherically bent analyzer crystal. Sample, crystal and detector and moved along this Rowland to change the Bragg angle and thus to perform and energy scan.

Sample, Analyzer, and Detectors for X-ray emission spectroscopy

Selected References

[1] J.C. Fuggle and J.E. Inglesfield, eds. Unoccupied Electronic States. Topics in Applied Physics. Vol. 69. 1992, Springer-Verlag: Berlin.

[2] F.M.F. de Groot, High-Resolution X-ray Emission and X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Chem. Rev., 2001. 101: p. 1779-1808.

[3] F.M.F. de Groot, Multiplet effects in X-ray spectroscopy. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2005. 249(1-2): p. 31-63.

[4] P. Glatzel and U. Bergmann, High resolution 1s core hole x-ray spectroscopy in 3d transition metal complexes - Electronic and structural information. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2005. 249: p. 65-95.

[5] F.M.F. de Groot and A. Kotani, Core Level Spectroscopy of Solids. Taylor and Francis, New York (2008)

[6] A. Meisel, G. Leonhardt, and R. Szargan. X-ray Spectra and Chemnical Binding, Chemical Physics Vol 37. Springer Verlag, 1989

[7] W. Schülke, Electron Dynamics by Inelastic X-Ray Scattering (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2007)

[8] J. Hoszowska, et al., Nucl. Instr. and Meth. A 376, 129 (1996)

[9] K. Sakurai and H. Eba, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. Part 1 38, 650 (1999)

[10] U. Bergmann and S. P. Cramer, in Crystal and Multilayer Optics (SPIE, San Diego, 1998), Vol. 3448, p. 198

[11] H. Hayashi, et al., J. Electron Spec. Rel. Phen. 136, 191 (2004)

[12] E. Welter, et al., J. Synch. Rad. 12, 448 (2005)

[13] S. Huotari, et al., Rev. Sci. Instrum. 77 (2006)

[14] A. C. Hudson, et al., Rev. Sci. Instrum. 78 (2007)

[15] J. P. Hill, et al., J. Synch. Rad. 14, 361 (2007)

Resonant Inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS)

The electronic states that give rise to the edge of an absorption spectrum are resonantly excited states that subsequently decay. The energy that is released in the decay process can be carried either by an electron that is promoted into the continuum (resonant Auger effect) or by a photon. A radiative decay after resonant excitation is in the literature referred to as resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS), resonant X-ray emission (RXES)or resonant X-ray Raman spectroscopy (RXRS). The combination of resonant excitation with emission detection bears some interesting physical phenomena such as interference effects, line narrowing and Raman-Stokes line shifts.[1-2]

RIXS can be used to study electronic excitations at energies much lower than the incident hard X-ray energy. This is due to the fact that the energy transfer - defined as the difference between incident and emitted energy - describes the electronic excitations. The energy transfer is equivalent to the final state energy of the excited electron configuration. It can be as low as a few meV or as high as several keV. In the former, the spectroscopy is sensitive to phonon excitations, very weak electron-electron or collective excitations. Final state energies of a few eV lie in an energy range that is equivalent to optical excitations directly probing the valence orbitals (but element-selectively). Higher final state energies of more the a few tens of eV contain a core hole in the final state.

Selected References

[1] A. Kotani and S. Shin, Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering spectra for electrons in solids. Reviews of Modern Physics, 2001. 73(1): p. 203-46.

[2] F. Gel’mukhanov and H. Ågren, Resonant X-ray Raman scattering. Physics Reports-Review Section of Physics Letters, 1999. 312(3-6): p. 91-330.

X-ray Raman Spectroscopy

X-ray Raman scattering (XRS) is non-resonant inelastic scattering of x-rays from core electrons. It is analogous to Raman scattering, which is a largely-used tool in optical spectroscopy, with the difference being that the wavelengths of the exciting photons fall in the x-ray regime and the corresponding excitations are from deep core electrons.

XRS is an element-specific spectroscopic tool for studying the electronic structure of matter. In particular, it probes the excited-state density of states (DOS) of an atomic species in a sample. As explained below, it allows access to very similar information as x-ray absorption spectroscopy.

XRS is an inelastic x-ray scattering process, in which a high-energy x-ray photon gives energy to a core electron, exciting it to an unoccupied state. The process is in principle analogous to x-ray absorption (XAS), but the energy transfer plays the role of the x-ray photon energy absorbed in x-ray absorption, exactly as with Raman scattering in optics where vibrational low-energy excitations can be observed by studying the spectrum of light scattered from a molecule.

Because the energy (i.e. wavelength) of the probing x-ray can be chosen freely and is usually in the hard x-ray regime, certain constraints of soft x-rays in the studies of electronic structure of the material are overcome. For example, soft x-ray studies may be surface sensitive and they require a vacuum environment. This makes studies of e.g. many liquids impossible using soft x-ray absorption. One of the most notable applications in which x-ray Raman scattering is superior to soft x-ray absorption is the study of soft x-ray absorption edges in high pressure. Whereas high-energy x rays may pass through a high-pressure apparatus like a diamond anvil cell and reach the sample inside the cell, soft x-rays would be absorbed by the cell itself.

History

In his report of finding of a new type of scattering, C. V. Raman proposed that a similar effect should also be found in the x-ray regime. Around the same time, B. Davis and D. Mitchell reported in 1928 on the fine-structure of the scattered radiation from graphite and noted that they had lines that seemed to be in agreement with carbon K shell energy. Several researchers attempted similar experiments in the late 1920s and early 1930s but the results could not always be confirmed.

Often the first unambiguous observations of the XRS effect is credited to K. Das Gupta (reported findings 1959) and Tadasu Suzuki (reported 1964). It was soon realized that the XRS peak in solids was broadened by solid-state effects and it appeared as a band, with a shape similar to that of a XAS spectrum. The potential of the technique was limited until modern synchrotron light sources became available.

This is due to the very small XRS probability of the incident photons, requiring radiation with a very high intensity. Today, the XRS technique is rapidly growing in importance. It can be used to study near-edge x-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS/XANES) as well as extended x-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS).

Brief theory of XRS

XRS belongs to the class of non-resonant inelastic x-ray scattering, which has a cross section of

Here, \((\rm{d} \sigma / \rm{d} \Omega )_{\rm Th}\) is the Thomson cross section, which signifies that the scattering is that of electromagnetic waves from electrons. The physics of the system under study is contained in the dynamic structure factor \(S(\bf{q},\omega)\), which is a function of momentum transfer \(\hbar \bf{q}\) and energy transfer \(\hbar\omega\). The dynamic structure factor contains all non-resonant electronic excitations, including not only the core-electron excitations observed in XRS but also e.g. plasmons, the collective fluctuations of valence electrons, and Compton scattering.

In the one-electron approximation, the dynamic structure factor is given by

where \(|i\rangle\) and \(|f\rangle\) mark initial and final states (with energies \(E_i\) and \(E_f\)), and \(\bf{r}\) is the electron position.

Similarity to x-ray absorption

It was shown by Yukio Mizuno and Yoshihiro Ohmura in 1967 that at small momentum transfers \(q = |\bf{q}|\) the XRS contribution to the dynamic structure factor is proportional to the x-ray absorption spectrum. The main difference is that while the polarization of light couples to the momentum of the absorbing electron in XAS, in XRS the momentum of the incident photon couples to the charge of the electron. Because of this, the momentum transfer direction of XRS plays the role of photon polarization of XAS.

As can be seen from the expansion of the exponent in the previous expression

at low \(\bf{q}\) dipolar transitions dominate, resulting in equivalent transitions as in x-ray absorption spectroscopy (the first term of the expansion (unity) does not contribute due to the orthogonality of the initial and final states):

In this low-\(q\) limit (the dipole limit), the dynamic structure factor is thus directly proportional to the x-ray absorption cross section (with \(\bf{q}\) taking the role of the polarization \(\hat{\epsilon}\)). In the case of K-shell XRS (or XAS), the spectra is proportional to the p-symmetry projected density of empty states (pDOS). With increasing momentum transfer also monopolar and quadrupolar transitions begin to contribute, adding weight from sDOS and dDOS to the XRS spectrum.

Selected References

Schülke. Electron dynamics studied by inelastic x-ray scattering. Oxford University Press, 2007

See also: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X-ray_Raman_scattering

X-ray and Neutron scattering, Pair Distribution Function (PDF)

The Pair Distribution Function (PDF) method uses neutron or X-ray scattering to measure the distribution of atom-atom distances in a sample. Whereas Bragg scattering typically measures only the most intense diffraction peaks (the Bragg peaks) to determine the long-range order, PDF measures the total scattering pattern including the diffuse or liquid-like scattering which is sensitive to all atom-atom correlations. PDF measurements are typically done on nano-scale crystallites or highly disordered materials to obtain information about short-range order. powdered sample quantitatively.

The PDF gives the probability of finding one atom a given distance away from another; peak positions therefore correspond to atom-atom mean separations and peak areas to atom-atom coordinations. Data may be analysed using ‘small box methods’, sometimes termed ‘real-space Rietveld’, or ‘big box’ methods such as reverse Monte Carlo (RMC) methods. In the latter, an ensemble of atoms are moved iteratively until good agrement is obtained with the total scattering data (in real and/or reciprocal space) and it is especially powerful for cases of substantial disorder, including amorphous materials. Further details are given here.

A comparsion of PDF and XAFS methods includes:

PDF is not atom specific, and so contains signals from all atom-atom pairs of atoms (the total pair distribution function) whereas EXAFS is sensitive only to the atoms surrounding the selected absorbing atom (the partial pair distribution function). Each has advantages and lends itself to different application areas. Note that, as with all X-ray scattering methods, it is possible to use resonant scattering methods to enhance or isolate the scattering contribution from one atomic species with PDF. Similarly, one can do selected isotopic replacement with neutron scattering to isolate the contribution from a single atom type.

Like EXAFS, PDF is a quantitativ measure of local structure. Data interpretation are robust and the PDF provides an unambiguous function for further study.

The typical length scale that can be probed and successfully analyzed with PDF is typically longer than for EXAFS. For EXAFS, unambiguous analysis past 5 Angstroms or so is challenging, while PDF can be sensitive up to 20 Angstroms or so.

Diffraction Anomalous Fine Structure (DAFS)

DAFS is the XAFS-like oscillations observed in the diffracted intensities of Bragg diffraction peaks.

Selected References

Diffraction anomalous fine structure: Unifying x-ray diffraction and x-ray absorption with DAFS L. B. Sorensen, Julie O. Cross, M. Newville, B. Ravel, J. J. Rehr, H. Stragier, C. E. Bouldin, and J. C. Woicik. Resonant Anomalous X-Ray Scattering: Theory and Applications Ed. G. Materlik, C. J. Sparks, and K. Fischer, North-Holland, pp. 389–420, (1994).

Analysis of Diffraction Anomalous Fine Structure Julie Cross’s PhD dissertation.